Dawn Purves reports on her LI-funded trip to Minnesota, USA to attend the International conference on Citizen Science

Dawn Purves, a PhD student from Kingston University’s landscape department, received funding from the Landscape Institute to attend the International Conference on Citizen Science in Minnesota, USA. Reflecting on her research and the conference, Dawn discusses community resilience and the ways in which low-impact sustainable urban drainage as a means of preventing localised flooding can be encouraged at multiple scales as climate change adaptation.

Citizen Science is globally assisted by three associations: the Citizen Science Association (CSA), with an American and Canadian focus; the European Citizen Science Association; and the Australian Citizens Science Association. Bi-annually, the Citizen Science Association holds a conference for four days, which this year was held in St Paul, Minnesota, attended by 500 delegates and, on the last day for an open event, the wider public.

The conference highlighted current misperceptions in that, despite policy and guidance emphasis upon public participation through localism, citizens are commonly not allowed to have scientific thought or a ‘brain’. (Dr Mark Edmunds, 2017). The keynote speeches, presentations and round tables emphasised that the time had come to overthrow those misperceptions, and to highlight the valuable roles that citizens play in problem-solving complex scientific issues. The Citizen Science Association conference illustrated many existing projects where this has occurred very successfully, both from top-down programs facilitated by scientists, to bottom-up initiatives by individuals in an effort to democratise science.

The conference illustrated that sometimes you have to take a stand and expose the injustices. It illustrated that citizen science can intervene, providing a symbiotic nature between citizens and scientists, and in so doing foster political engagement. It can play an important role in informing policy fostering environmental decision-making. You have to become a DIY citizen scientist – having your own question, building your research and developing answers.

400 abstracts were submitted by organisations, individuals and members, and over a six-month period reviewed by 300 member reviewers, alongside 200 posters. I was accepted by the Citizen Science Association to present a talk with four others under the overall title of environmental management. Landscape Institute funding enabled me to attend and present my research, which aligns current LI policy. The talk presented aspects from my PhD research illustrating the scope for broad Ecological Citizenship to facilitate low-impact sustainable urban drainage through re-framing the issues, facilitating solutions through active participatory social learning engagement and motivating collective responsibility and actions.

The talk focused on environmental decision-making: in particular how to inform decisions in a changing climate, and the role of motivating people to take more responsibility for global complex issues such as localised flooding, increasing populations and altered lifestyle patterns due to population migrations, causing densification and reductions in permeable surfaces that leads to increased instances of flooding. My talk illustrated the various roles where citizens could be encouraged to be involved in the process of planned climate change adaptation to localised flood prevention and in particular drew upon current research undertaken with Transition Cambridge in establishing a Learning to Stay Dry ‘Community of Practice’ sub-group, one that aims to facilitate a grass roots bottom-up engagement communication to the complex issues around flooding.

The conference enabled me to receive constructive criticism on the methods and processes of my research and to learn from other exemplar projects. The common themes illustrated at the conference were the potential for citizen involvement at data collection and modelling stages. It also highlighted current barriers faced, including a of lack of trust, limited available knowledge, no previous experience, legal and administrative barriers, general apathy and cultural barriers (Duke, 2017). But despite these negatives, it also provided many solutions to those issues, including the role of values in influencing decision making and how targeted projects focused on those who associate themselves Biospheric or Egotistic- interested in helping the environment can improve success rates. It illustrated wider research that is looking at the roles of environmental identity and participation success, exploring how identities alter through the lifetime of the project, a key attribute of my research. It also illustrated the role of ‘learning by doing’ or ‘learning from others’ through communities of volunteers undertaken at micro and macro levels, illustrating ‘groupiness’ of the project and its effect in influencing social norms (again aligning my research) which looks at the role and scope of social learning in overturning apathy and lack of responsibility to flood prevention in favour of LISUD, and fostering ecological norms. Finally, it looked at ‘framing’ and the way the issues are framed, illustrating how rhetoric presentation determines desired outcomes.

My research: a brief overview

Evidence (base-adaptation.eu, 2015) points to small-scale bottom-up actions being important in flood prevention. However empirical work carried out by Transition Cambridge sub-group ‘Learning to stay dry’ and other recent literature (Somerville & Hassol, 2011) point to indifference. Column inches and top-down action follow large-scale disaster – but small-scale prevention is a ‘Cinderella’ relative.

Flooding is increasingly seen as a significant problem around the world, costing billions each year to rectify.

The causes of flooding are well known. These include increased populations, and population migrations, which cause densification and losses of permeable surfaces, and ‘global weirding’ (Lovins, 2002), where altered rainfall patterns lead to instances of heavy rain.

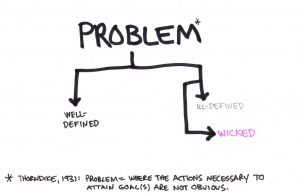

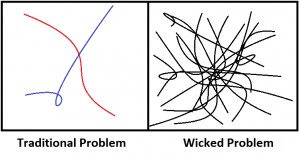

‘Super-wicked’ problems (Lazarus, 2010) such as climate change have become a significant problem in our cities causing increased property and neighbourhood flooding. If flooding is to be tackled in a sustainable way and increased community resilience as called for by the European Water Framework Directive 2015, putting the citizen back at the forefront of sustainability; then each of us needs to refocus our behaviour rather than being reliant on over stretched Local Government Authorities of Municipalities to solve those issues for us. Current legislation in the UK recommends maintaining pre-development flow-off rates for all new developments through a promotion of both hard-engineered solutions and green sustainable urban drainage measures. These measures are enforced and guided through the planning system. But in parts of the world where these regulations and controls are less evident, or within existing urban areas flooding is still unresolved. In these areas, community resilience is vital. Many local organisations exist which bring communities together to resolve specific issues, such as residents’ associations, transition groups, business investment districts (BID) and flood groups.

This research looks at which is more successful at lessening localised flooding and demystifying water management to increase community resilience. Either top-down approaches of legislation, policy, taxation and incentivisation, or bottom-up grass roots broad ecological citizenship. Community resilience is defined as ‘The ability of community members to take meaningful, deliberate, collective action to remedy the impact of a problem, including the ability to interpret the environment, intervene, and move on.’ (Pfefferbaum, 2005). Broad ecological citizenship is a concept that we are all an integral part of our environment, recognition that our future depends on how we care for our ecosystems, and a sense of responsibility that lead to action on behalf of the environment.

The proposition of the research is that issues surrounding flooding that currently restrict engagement and motivation could be re-framed around broad ecological citizenship and a moral judgement system focusing on our values, beliefs and attitudes, so that citizens could be motivated into taking more collective responsibility towards devising appropriate low impact sustainable urban drainage measures. It proposes that a different approach to communication is needed drawing on the wider issues associated with climate change, identification, social justice, ecological footprints and ecosystem services. By communicating the issues through active participatory social learning within ‘communities in practice’, meaningful participatory planning could occur. Through surveys and focus group interviews undertaken for this research in 3 different flood-prone areas across the UK these ‘communities of practice’ – ‘groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and who interact regularly to learn how to do it better’ (Lave & Wenger, 1991). can also play a further role in facilitating and motivating community resilience, enabling practitioners to take collective responsibility for managing the knowledge they need.

How could the profession adapt in light of these findings?

Flooding affects us all. In the UK, we have recently witnessed devastating examples of flooding from the Somerset levels in the winter 2013-2014 to Penrith in Cumbria in the winter of 2015-16. But this is not only affecting the UK, with many instances around the world re-emphasizing the urgent need for action. With changes in climate and global warming it is not enough to wait for the next flood, we need to undertake greater planned adaptation measures in the form of retrofit low impact sustainable urban drainage.

These measures have been seen to be effective, but are currently not being installed in great enough numbers to have significant effect. As Landscape Architects and built environment professionals we have great opportunities to promote these measures, both on new developments and existing areas being regenerated.

Current policy facilitates participation in decision making through the Localism agenda and the Flood and Water Management Act via the promotion of community flood groups. If more of these LISUD measures are to be implemented rather than hard engineered solution, measures that demystify water management and provide better collective understandings around the issues and solutions, then Landscape Architects need to facilitate greater collective responsibility for planned adaptation and in particular at a grass roots bottom up level, through property, street and neighbourhood level LISUD measures as seen at Cloudburst Copenhagen, Rainproof Amsterdam and Climate proof Zoho, Rotterdam.

It is no longer acceptable to assume others will protect us, either financially or morally. We all need to do our bit, and as Landscape Architects we are ideally placed both to motivate community groups and local organisations to understand the issues around super wicked problems and, via active participatory social learning with stakeholders, develop LISUD solutions that provide a legacy for future generations.

Bibliography

- Somerville, R.C.J and Hassol, S.J., 2011. Communicating The Science of Climate Change, [Online] Available at:< https://www.climatecommunication.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Somerville-Hassol-Physics-Today-2011.pdf >[Accessed 10 December 2014].

- Lave, J & Wenger, E., 1991. Situated Learning. Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lazarus, R.J., 2010. Super Wicked Problems and Climate Change: Restraining the Present to Liberate the Future, [Online] Available at:<http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1152&context=facpub> [Accessed 20 January 2013].

- Pfefferbaum, B. J. et al., 2005. Building Resilience to Mass Trauma Events. In L. S. Doll, S.E. Bonzon, J.A. Mercy & D. A . Sleet, eds., Handbook on Injury and Violence Prevention Intervention. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers.