Landscape architect Tom Turner shares his thoughts on how professional interventions could alleviate flood risk in the capital

The Thames Barrier closed four times in the 1980s, 35 times in the 1990s, and 50 times in the year 2014. Is this because of climate change and sea level rise? No. Is it because London’s rainfall has increased? No. Is it because too little has been done about sustainable urban drainage (SuDS)? Yes.

The area of impermeable surfacing in London keeps increasing, and the volume of surface water discharge increases with it. Half the Barrier closures are now at low tide – to keep the water out of London so that the tideway can be used as a stormwater detention facility. This is required because impermeable surfacing and new drains are accelerating surface water runoff throughout the Thames catchement. The worsening of London’s flood problem is caused by bad planning and bad design, mostly by architects and engineers on development projects.

So what can be done? In a lecture to the London Parks and Gardens Association on 21 June 2017, I made the following suggestions:

Better flood management facilities in parks

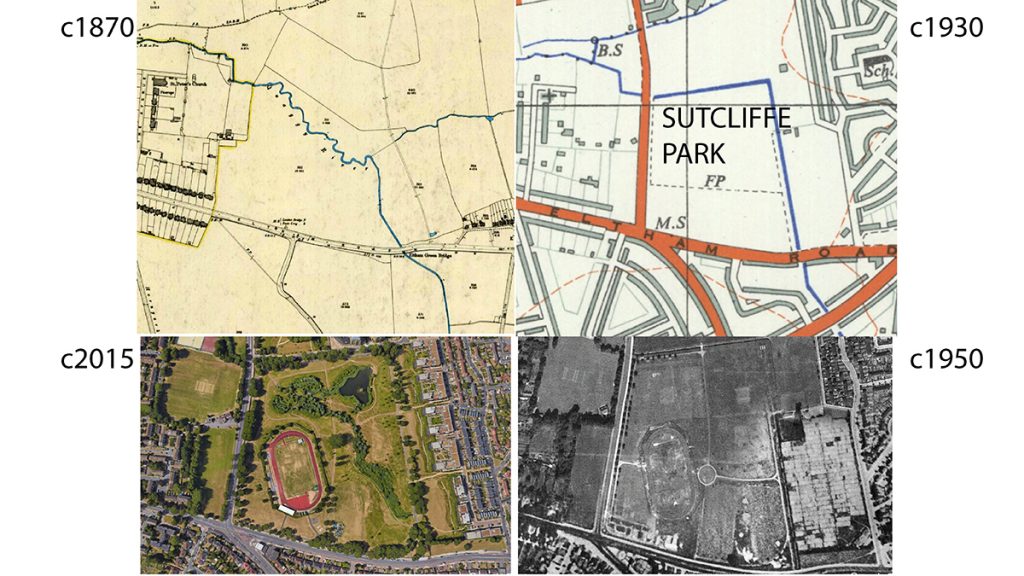

Parks should have many more rain gardens, storm detention areas and storm infiltration areas installed as income-generating facilities. Spending flood defence money in this way is much better than spending it on madcap projects like the Thames Tideway Tunnel. Even the chair of the panel that recommended the Tideway Tunnel now sees it as a waste of money. The best example of storm detention I know of in a public open space in London is Sutcliffe Park in Greenwich, designed by landscape architects working for the National Rivers Authority, which became the Environment Agency and implemented the project.

Green roofs

Cities with flood problems should adopt ambitious Green Roof Strategies. The US Environmental Protection Agency has found that green roofs can ‘remove 50% of annual rainfall runoff volume through retention and evapo-transpiration’ and that ‘rainfall not retained is detained, effectively increasing the time to peak, and slowing peak flows for a watershed’. Green roofs are a public good (as well as being private goods) and the creation of public goods is one of the distinguishing characteristics of the landscape profession.

Olympic Park flood detention

The Queen Elizabeth II Olympic Park could have a large flood detention facility, learning from the Grüner See (Green Lake) in Styria, Austria, which gets 10 metres deeper in spring. Such was the popularity of the lake, particularly with scuba divers, that all watersports are prohibited to prevent damage to the environment.

Better flood storage in the Thames Path

A landscape strategy to increase the flood storage capacity of the Thames Tideway should be developed and implemented. Sections of the Thames Path can be allowed to flood, as can public open spaces beside the river. Owners of riverside homes in high flood-risk areas should be encouraged to flood-proof their own houses and gardens, as the residents of Richmond and Strand on the Green already do. The advantages of this policy, compared with flood walls and berms, are that they do much less damage to the capacity of flood plains than bunds, and they do not have to be funded by taxing people who have not chosen to live in flood plains.

Landscape professionals should publicise the fact that while engineers want to get water off the land, we want to keep water on the land. We need to work closely with RTPI members on this. Planners have the power to persuade landowners and developers to create public goods. Engineers tend to be single-minded, and architects tend to work on projects that create private goods. Landscape professionals often have two clients: the landowner and the wider community.

Tom

Thanks for such a concise summary of such a big, complicated issue. I was fascinated by the statement about the Thames Barrier: “Half the Barrier closures are now at low tide – to keep the water out of London so that the tideway can be used as a stormwater detention facility.”

This made me look up a few references:

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/the-thames-barrier

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-26133660

But if you have any better references it would be good to have a link.

This will become my new favourite opening gambit in any debate about SuDS: “Who knows what the Thames Barrier is for?” Answer – not what most people think!

Thanks Bill.

Here is a Guardian ref https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/feb/19/thames-barrier-how-safe-london-major-flood-at-risk

And Wiki has a list of reasons for closing the Barrier

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thames_Barrier

Tom -Thanks for introducing this subject into the conversation with landscape architects. The principles you describe have been approached in depth and as a more recent series of recommendations by CIRIA in their design for exceedance publications http://www.susdrain.org/delivering-suds/drainage-exceedance/Encouraging-uptake/Background-outputs

These publications and others on SuDS do contradict the sweeping statement that “engineers want to get water off the land, we want to keep water on the land”. The case studies are an interesting range of solutions and many could have done with the input of the landscape profession. But the principle of finding space for water and developing the right strategies along the way is what emerges strongly.

You see it isn’t about single minded engineers vs open minded landscape architects; us vs them… We NEED – absolutely MUST work together to share our expertise. In fact it is engineers that have traditionally been the drivers behind sustainable drainage and keeping water on the surface. The landscape profession has been slower to catch up. Working in isolation leads to assumptions, errors and ultimately a reduction in public confidence in managing water on the surface; especially when we are seeking to win hearts and minds in the sensitive area of flood risk management. So lets move on and see collaborative professional partnerships flourish and recognise we can’t do this alone as a profession. There are Engineers and other professionals aplenty out there who support an holistic ethos and they are increasing in numbers and what better realm to share our expertise but in the green infrastructure design.